Bonds of Dissent: William Penn (1681)

William Penn was the son of an English admiral and a royalist supporter of Charles II and James II before the Glorious Revolution. An imprisoned debtor at the end of his life, his background is one of landed wealth in Ireland and royal favor at court. Much to his father’s displeasure, Penn became a convinced Quaker at the age of 22.

William Penn was the son of an English admiral and a royalist supporter of Charles II and James II before the Glorious Revolution. An imprisoned debtor at the end of his life, his background is one of landed wealth in Ireland and royal favor at court. Much to his father’s displeasure, Penn became a convinced Quaker at the age of 22.

For most of the seventeenth century, Quaker meetings were made illicit by a series of Conventicle Acts. Despite his privileged background, Penn was arrested and imprisoned multiple times for attending or leading Quaker meetings. His experiences with detention and bail inspired him and fellow Quaker lawyer Thomas Rudyard to include a right to bail in the Frame of Government, the founding document of colonial Pennsylvania. This document was highly influential in the formation of future state constitutions, making Penn’s experience with arrest and bail of great importance.

Penn’s Experience with Arrest and Bail

Penn’s first arrest occurred in October of 1667, shortly after he began to consistently attend Quaker meetings in Cork, Ireland. After Penn forcibly ejected a soldier seeking to cause trouble at a meeting, the soldier reported the elicit meeting to a local magistrate who, no doubt aware of Penn’s social status, told Penn he would not be jailed as the magistrate “did not think him a Quaker.” Penn retorted that he was a Quaker and would share in his fellows’ imprisonment. He was detained with eighteen others for violating the 1664 Conventicles Act. Penn wrote an indignant letter to the Earl of Orrery, a local magnate, on November 4, 1667, his first known writing on religious toleration. Orrery ordered the prisoners’ release, purportedly before he received Penn’s letter.1 The most recent of Penn’s biographers figures the Cork imprisonment could not have lasted more than a day or two.1Andrew R. Murphy, William Penn: A Life (2018), 48–50.

The second imprisonment in the Tower of London was significantly longer. From December 1668 to July 1669, Penn was jailed for publishing a theological polemic titled The Sandy Foundation Shaken. He was held “close,” meaning without visitors, without movement from his apartment, and without opportunity for bail. Penn wrote his most notable works on religious toleration during his eight month imprisonment, concluding with a tract that affirmed the divinity of Christ and so satisfied the authorities that he need not be detained any further for the blasphemy of The Sandy Foundation. Penn was released “into the custody of his father.”2Id. at 58–60. For the release order, see Papers of William Penn I: 97.

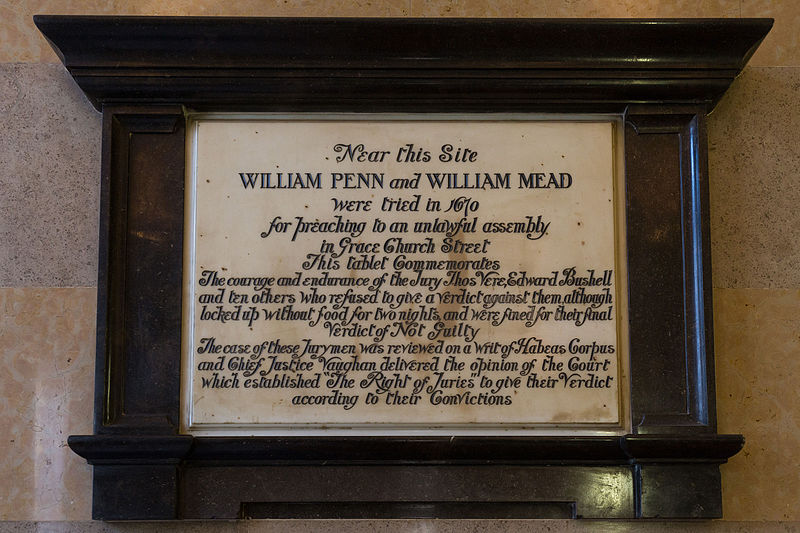

Penn’s next arrest was one of the most significant in legal history. On August 14, 1670, Penn and another Quaker William Mead were arrested for preaching in contravention of a renewed 1670 Conventicle Act. They were held in Newgate Prison for two weeks waiting to be tried at the Old Bailey. Famously, the jury refused to convict, and the judges’ fine on the jury was eventually overturned in the famous Bushel’s Case.3On the foundational significance of the case, see Kevin Crosby, Bushell’s Case and the Juror’s Soul, 33 J. of Leg. Hist. 251 (2012); Simon Stern, Between Local Knowledge and National Politics: Debating Rationales for Jury Nullification after Bushell’s Case, 111 Yale L.J. 1815 (2002). Penn was returned to detention nevertheless, in contempt for refusing to doff his hat to the court. Penn steadfastly refused to pay the stiff fine that could have cured the contempt. But a month later, with his father on his deathbed and the prospect of the two remaining forever unreconciled, Penn appears to have allowed the fine to be paid.4Murphy, Life, 74–79. See also Scott Turow, Order in the Court, N.Y. Times Mag., April 18, 1999 (arguing the Penn-Mead trial “probably did more than any other case to refine the trial tradition in England the United States”).

Penn’s next arrest was one of the most significant in legal history. On August 14, 1670, Penn and another Quaker William Mead were arrested for preaching in contravention of a renewed 1670 Conventicle Act. They were held in Newgate Prison for two weeks waiting to be tried at the Old Bailey. Famously, the jury refused to convict, and the judges’ fine on the jury was eventually overturned in the famous Bushel’s Case.3On the foundational significance of the case, see Kevin Crosby, Bushell’s Case and the Juror’s Soul, 33 J. of Leg. Hist. 251 (2012); Simon Stern, Between Local Knowledge and National Politics: Debating Rationales for Jury Nullification after Bushell’s Case, 111 Yale L.J. 1815 (2002). Penn was returned to detention nevertheless, in contempt for refusing to doff his hat to the court. Penn steadfastly refused to pay the stiff fine that could have cured the contempt. But a month later, with his father on his deathbed and the prospect of the two remaining forever unreconciled, Penn appears to have allowed the fine to be paid.4Murphy, Life, 74–79. See also Scott Turow, Order in the Court, N.Y. Times Mag., April 18, 1999 (arguing the Penn-Mead trial “probably did more than any other case to refine the trial tradition in England the United States”).

Penn’s freedom after the Conventicle trial was brief. In February 1671, He was arrested yet again for illicit preaching, this time under The Five Mile Act which provided only for a bench trial. Without the public spectacle of his trial with Mead, Penn was quietly tried and sentenced to six additional months in Newgate.5Id. 85–86.

Penn’s struggles with pretrial detention and bail did not end with religious persecution. During and after the fall of James II, Penn was arrested in June 1689 and released on bail in July, then re-arrested in September and re-released in October of that year. In 1690, Penn was imprisoned from July to November after his request for bail was denied. In all these cases Penn was suspected of being a Jacobite traitor. Though he did not mention bail, Penn chided the Pennsylvania Assembly in November 1690 for issuing warrants of arrest against its members when the Frame had not granted the legislature powers of arrest or contempt.

Penn’s life effectively ended in prison as well, but this time because of civil imprisonment for debt. For nearly the entirety of 1708, Penn was confined within the precinct of the Fleet Prison, a form of house arrest that permitted Penn to maintain a private apartment. Although Penn lived another decade, his health and mind broke shortly after his release from this last imprisonment.

Penn’s Theory of Fundamental Law and Liberties

While Penn did not leave any systematic treatments of his thought on government and liberty, his views were able to be pieced together from his arguments during the trial with Meade and from other polemical works. Penn’s intellectual biographer, Andrew Murphy, has demonstrated that Penn’s views on government and liberty are surprisingly relevant to twenty-first-century thought. In an age marked by a rising theory of Parliamentary supremacy, “Parliament was always understood,” in Penn’s writings, “as ultimately bound by fundamental law.”

“Fundamental law” which Penn also refers to as “people’s ancient and just liberties,” inhered in liberties possessed by Englishmen both at home and abroad. These liberties cannot be taken away by either Parliament, the Crown, or their agents.Although it is usually anachronistic to ascribe a belief in “fundamental rights” to pre-eighteenth-century theorists, Penn used these exact words and explained what he meant by them in a tract outlining the three fundamental rights of the Commons: “life, liberty, and estate.” This conception of fundamental law meant that even acts of positive lawmaking like legislation from Parliament might ultimately be unlawful. For example, Penn proposed that magistrates should not strictly adhere to the Conventicle Acts, but instead should question whether the legislation was valid according to the fundamental laws. For Penn, the essential source of fundamental law was Magna Carta. During his trial with Mead, Penn continually appealed to Magna Carta (or Lord Coke’s commentaries on the same) for his proof-text both that the proceedings were in violation of fundamental law and that the jury had the right to nullify the unjust charge regardless of the factual record. Penn was continually outraged that his arrests violated the letter and spirit Magna Carta’s provision that “[n]o free man shall be seized or imprisoned . . . except by the lawful judgment of his equals or by the law of the land.” Penn quoted this clause at least five separate times in the transcript of his trial with Mead. Penn’s chief complaint about the trial with Mead was “First, that the prisoners were taken, and imprisoned, without presentment of good and lawful men of the vicinage, or neighbourhood, but after a military and tumultuous manner, contrary to the grand charter.” Penn, of course, was making this argument in a jury trial. The implication was that any imprisonment before trial therefore inflicted punishment without a lawful verdict, in contravention of Magna Carta.

Penn’s polemical works leave no indication of whether such pretrial punishment might be necessary to incapacitate notorious offenders, but as we shall see his constitution for Pennsylvania left very little ground for magistrates to impose pretrial detention. What is clear enough is that our modern doctrine that “regulatory detention” before trial does not constitute punishment would have struck Penn as an absurd fiction. Imprisonment was imprisonment. Detention by the state divested the accused of fundamental rights of life, liberty, and property and was, therefore, unlawful apart from conviction by the jury.

Penn’s Frame of Government

In 1680, Penn asked King Charles II to grant him a colony in America as a way for the crown to pay off significant debts owed to Penn’s family. Numerous Quakers were drawn to colonization in the areas which would become New Jersey, as they saw it as the best way to practice their religion without interference and create a perfect society to serve as an example to the rest of the world. In March 1681, his request was approved and he promptly composed the Frame of Government, the colony’s constitution.

Penn composed the Frame of Government through numerous drafts between March 1681 and April 1682. Thomas Rudyard, a Quaker lawyer who had provided legal advice to Penn in his trial against Mead at the Old Bailey, joined in to help with the writing near the end of the process. Rudyard’s first draft included a bail clause, which the two authors refined to provide: “All prisoners shall be Bailable by sufficient sureties, unless for Capital offences where the proof is evident & or the presumption great.”

The clause adopted marked a compromise between English practice and Quakers’ ideals. Penn had contributed a clause to the Fundamental Laws of West New Jersey forbidding arrest or imprisonment “for or by reason of any debt, duty, or thing whatsoever (cases felonious, criminal and treasonable Excepted).” This protected misdemeanor defendants from having to post bail, but allowed magistrates to bail or detain in cases of felony. Rudyard proposed an article that more closely followed Magna Carta: “That all persons for Criminal Causes shall & may be bayled by sufficient suretyes, untill Conviction by the verdict of 12 persons of the neighbourhood.” Such a clause would have provided a right to bail in every case and codified Penn’s view that no imprisonment could be ordered without a jury verdict. The final draft blended the two approaches, magistrates retaining some discretion to deny bail only in capital cases.

Penn and Rudyard’s bail clause was radical in its context. While Ward’s clause for Massachusetts provided a right to bail “unless it be in Crimes Capital”, the list of capital crimes in Puritan Massachusetts was quite long. Penn, however, only limited capital punishment to intentional murder. He opposed blood punishments and imprisonments of all types, and “considering the tenderness of the holy merciful Christian Law,” sought to replace them with restitution and bonded labor in Pennsylvania. An early draft of his constitution mentioned “Gaols of Nations filled with Prisoners for Debts that they can never Pay and so their Confinement can only be the effect of an unprofitable revenge.”. Thus, Penn restricted imprisonment for debt and replaced it with limited periods of servitude. This would significantly broaden the pool of available sureties for any given defendant.

In correspondence with Irish Quakers, Penn wrote that he intended “to leave myself and successors no power of doing mischief.” He imposed self-restraints on government, such as the bail clause, which was to be enforced alongside others. He mandated frequent, local court sessions “to prevent tedious and expensive Pilgrimages” and ensure justice was done quickly and impartially. Every person could “freely Plead” claims without lawyers, and courts were to inform them of their rights. Penn also stringently protected the right to a jury and access to the writ of habeas corpus to prevent unlawful imprisonment.

Penn aimed to protect citizens from being jailed on mere accusation. Convinced that the fundamental law of Magna Carta required no less, he curtailed the government’s ability to detain prior to a jury verdict. Arrestees had a right to bail in all but a narrow category of capital cases, with magistrates having discretion to admit to bail. Swift access to habeas corpus and legal advice for those without counsel were also implemented to ensure the right to bail wasn’t just a paper promise.

The Scope and Significance of Penn’s Model

Every state that joined the Union after 1789 (except West Virginia and Hawaii) guaranteed a right to bail in their original constitutions, closely following the text of Penn’s Frame. This clause was also incorporated into the Northwest Ordinance of 1787 and the Judiciary Act of 1789, making it the rule for federal territories and federal procedure.

The clause was broadly supported at the time of the Founding, but its destiny as the “consensus text”6Matthew J. Hegreness, America’s Fundamental and Vanishing Right to Bail, 55 Ariz. L. Rev. 909 (2013). was not yet clear in 1792, when the Bill of Rights was ratified. Every new state incorporated it in their constitution, but not all old states did. New York, New Hampshire, Maryland, Virginia and South Carolina followed the common law model through most or all of the nineteenth century. Massachusetts and Pennsylvania retained the clause at the time of the Founding, and North Carolina’s Revolutionary Era constitution (which was retained until after the Civil War) also included it. Connecticut, Delaware and Rhode Island adopted the clause after the federal Constitution was ratified – Delaware immediately and Rhode Island in the mid-1840s. Penn instigated the first legislation of East Jersey, containing his drafted clause, but New Jersey’s Revolutionary constitution omitted it. Penn’s clause finally returned in 1844 when New Jersey adopted its first state constitution.

In sum, about half of the new nation and the federal government recognized the right to bail at the time of ratification, while the other half followed the English common law model. If one considers the Founding Era to have run until the Madison Administration, the proportion quickly shifted in favor of Penn’s model, with Delaware, Connecticut, and all states admitted from Vermont onwards adopting it.

The system of bail was rooted in religious dissenters’ claims of religious liberty. A state that could jail someone on a mere accusation was a state that could—and did—haul disfavored worshippers into dungeons, separate pastors from their flocks, and punish private belief as blasphemous with or without trial. Penn and the other original dissenters believed their approach to bail was the only legitimate outworking of the fundamental law of England, from Magna Carta, that no free man could be detained and punished without—or before—trial by jury. A government based on fundamental law was one in which official discretion—the rule of will—had to be restrained.

References

- 1Andrew R. Murphy, William Penn: A Life (2018), 48–50.

- 2Id. at 58–60. For the release order, see Papers of William Penn I: 97.

- 3On the foundational significance of the case, see Kevin Crosby, Bushell’s Case and the Juror’s Soul, 33 J. of Leg. Hist. 251 (2012); Simon Stern, Between Local Knowledge and National Politics: Debating Rationales for Jury Nullification after Bushell’s Case, 111 Yale L.J. 1815 (2002).

- 4Murphy, Life, 74–79. See also Scott Turow, Order in the Court, N.Y. Times Mag., April 18, 1999 (arguing the Penn-Mead trial “probably did more than any other case to refine the trial tradition in England the United States”).

- 5Id. 85–86.

- 6Matthew J. Hegreness, America’s Fundamental and Vanishing Right to Bail, 55 Ariz. L. Rev. 909 (2013).