Bonds of Dissent: Nathaniel Ward (1641)

Nathaniel Ward came to the American colonies to escape the persecution of Puritans in England. He joined the Massachusetts Bay Colony at a time of controversy over the future shape of its legal order, and in his contribution to the colony’s legal struggles, Ward wrote America’s first bail reform statute.

Ward was hardly a liberal reformer. As characterized by Samuel Eliot Morison, Ward had “three chief antipathies: religious toleration, the Irish, and women.”1Samuel Eliot Morison, Builders of the Bay Colony 233–34 (1930). James Kendall Hosmer calls him “the raciest and most entertaining, if the narrowest and most intolerant, of the writers and speakers of New England.”2The phrase appears in an editorial footnote in 1 Winthrop’s Journal: History of New England, 1630–1649, at 36 n.1 (James Kendall Hosmer ed., 1908). But Ward’s strict Puritan commitments instilled in him, at the same time, a deep disdain for arbitrary government, and from his hand emerged a basic law that was, as Morison adds, “enlightened” and a “credit” to any seventeenth century commonwealth.3Morison, 234.

Ward’s Background

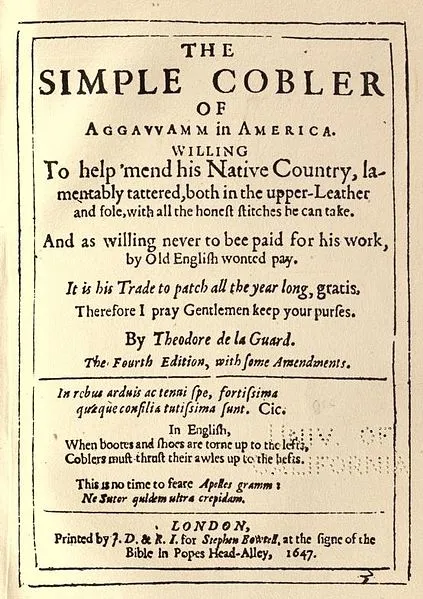

Nathaniel Ward arrived in Massachusetts Bay in 1634, at the age of fifty-five, and settled in the remote outpost of Ipswich.4Id. at 223, 226. An established Puritan, Ward had by then had a lengthy career in law and religion. He earned his law degree from Emmanuel College, Cambridge, in 1603, a “nursery of Puritans,” where he likely received a classical education complete with philosophy, logic, and rhetoric, and studies of the Bible and Calvin.5John Ward Dean, A Memoir of the Rev. Nathaniel Ward, A.M., Author of The Simple Cobbler of Agawam in America 20 (1868); Jean Béranger, Nathaniel Ward 48 (1969); see also Scott A. McDermott, Body of Liberties: Godly Constitutionalism and the Origin of Written Fundamental Law in Massachusetts, 1634–1666, at 23–50 (Ph.D. diss., Saint Louis University, 2014) (describing a “Protestant Scholastic” worldview of the early seventeenth century). In his later work The Simple Cobler of Agawam in America, Ward commented that he had read “almost all the Common Law of England, and some Statutes.”6Nathaniel Ward, The Simple Cobler of Aggawam in America 60 (P.M. Zall ed., Univ. Nebraska Press 1969) (1647). After practicing law in London for ten years, he took off to travel the European continent. In Heidelberg, he came under the influence of prominent Calvinist theologian David Pareus and was persuaded to enter the ministry.7Morison, 220–21. Ward’s first ministerial post was in Elbing, Prussia, where he saw “first-hand . . . what the Counter-Reformation meant.”8Id. at 221. John Ward Dean comments that “his charity [toward other religions] does not appear to have been enlarged by his experience abroad.” Dean, 10.

Ward returned to England in 1624 and came under the patronage of Sir Nathaniel Rich, a man of “Puritan tendencies,” who made him rector of Stondon Massey in Essex.9Dean, 31; Morison, 222. Though Ward did not experience religious persecution even approaching that of Penn, his Puritanism was not welcomed by the Anglican authorities, and royal sympathies were shifting further from the Puritans.10John Spurr, English Puritanism, 1603–1689, at 81 (1998). The looming hostility towards Puritanism did not stop Ward in 1624 from seeking the attention of Parliament—to report Richard Montagu for his apparently popish sympathies.11Id. at 81–82; McDermott, 86. In the meantime, it appears that Ward’s powerful connections as a man of the world, and in particular the patronage of Rich, sheltered him from the prelates.12Morison, 222; Dean, 31. In 1633, however, William Laud was named Archbishop of Canterbury and began to deal more harshly with the Puritans—imposing ritual and silencing their preaching. A “full tide of emigration” to the Massachusetts colony set in.13George Lee Haskins, Law and Authority in Early Massachusetts 60 (1960). Ward was excommunicated by Laud and joined the mass exodus.14Morison, 222.

The Legal, Political, and Religious Situation of the Massachusetts Bay Colony

The early Massachusetts Bay Colony into which Ward entered was characterized by several important legal, political, and religious dynamics. Two fundamental concerns stand out. First, the colony was an essentially religious endeavor. Soon after the Massachusetts Company was chartered, initially with commercial purposes, several English Puritans identified an opportunity to turn the project to religious ends. They managed to transfer management of the company from London to New England and merge management with the colonial government.15Haskins, 11–12. Because of this distance, Massachusetts Bay was “freer to depart from English ways in developing its laws and instruments of government” than the other early colonies.16Id. at 4; see also id. at 114–15 (describing the colony’s relatively autonomous legal development). The Puritans’ political vision was informed by their own adaptation of traditional Calvinist covenant theology.17John Witte, Jr., The Reformation of Rights: Law, Religion, and Human Rights in Early Modern Calvinism 289 (2007); Avihu Zakai, Theocracy in Massachusetts: Reformation and Separation in Early Puritan New England 23 (1994); Haskins, 15, at 19 (“[T]he covenant was more than a social compact between men; it was a compact to live righteously and according to God’s word. God was therefore viewed as a party to the covenant.”). The Puritan covenant of works was a natural relation between God and humans, inaugurated in Adam as the federal head of humanity, and it “instituted basic human relationships of friendship and kinship, authority and submission.”18Witte, 289–90. Witte distinguishes the Puritans’ view from traditional Calvinist understandings, which saw the covenant of works as existing between God and the chosen people of Israel. Id. The covenant of grace was extended to the elect by the sacrifice of Christ as the second Adam. The covenantal worldview saw Christian political society in an integrated and corporative light; it called for the total commitment of life to the achievement of the Christian polity while legitimating the godly authority of civil rulers and the just separation of social functions and roles.19McDermott, 9–10; Haskins, 16 (“[Puritanism] assumed that its disciplines would regulate not only their own conduct but that of others, so that the world could be refashioned into the society ordained by God in the Bible.”); id. at 17 (noting Winthrop’s view that Christian liberty could only be maintained by subjection to authority); see also Note, The Rule of Law in Colonial Massachusetts, 108 U. Pa. L. Rev. 1001, 1035 (1960) (describing Winthrop’s “belief that government was principally limited by the ruler’s conscience and self-restraint”). In Massachusetts Bay, “covenant was used to strengthen the authority of the state,” for in submitting to just government the members of the community “subjected themselves to obedience to God.” Indeed, “[c]arried into practice in Massachusetts, these doctrines resulted in a government in which authority was jealously held by the magistrates, intent upon carrying out the holy purposes of God’s word as expressed in the Bible.”

The early Massachusetts Bay Colony into which Ward entered was characterized by several important legal, political, and religious dynamics. Two fundamental concerns stand out. First, the colony was an essentially religious endeavor. Soon after the Massachusetts Company was chartered, initially with commercial purposes, several English Puritans identified an opportunity to turn the project to religious ends. They managed to transfer management of the company from London to New England and merge management with the colonial government.15Haskins, 11–12. Because of this distance, Massachusetts Bay was “freer to depart from English ways in developing its laws and instruments of government” than the other early colonies.16Id. at 4; see also id. at 114–15 (describing the colony’s relatively autonomous legal development). The Puritans’ political vision was informed by their own adaptation of traditional Calvinist covenant theology.17John Witte, Jr., The Reformation of Rights: Law, Religion, and Human Rights in Early Modern Calvinism 289 (2007); Avihu Zakai, Theocracy in Massachusetts: Reformation and Separation in Early Puritan New England 23 (1994); Haskins, 15, at 19 (“[T]he covenant was more than a social compact between men; it was a compact to live righteously and according to God’s word. God was therefore viewed as a party to the covenant.”). The Puritan covenant of works was a natural relation between God and humans, inaugurated in Adam as the federal head of humanity, and it “instituted basic human relationships of friendship and kinship, authority and submission.”18Witte, 289–90. Witte distinguishes the Puritans’ view from traditional Calvinist understandings, which saw the covenant of works as existing between God and the chosen people of Israel. Id. The covenant of grace was extended to the elect by the sacrifice of Christ as the second Adam. The covenantal worldview saw Christian political society in an integrated and corporative light; it called for the total commitment of life to the achievement of the Christian polity while legitimating the godly authority of civil rulers and the just separation of social functions and roles.19McDermott, 9–10; Haskins, 16 (“[Puritanism] assumed that its disciplines would regulate not only their own conduct but that of others, so that the world could be refashioned into the society ordained by God in the Bible.”); id. at 17 (noting Winthrop’s view that Christian liberty could only be maintained by subjection to authority); see also Note, The Rule of Law in Colonial Massachusetts, 108 U. Pa. L. Rev. 1001, 1035 (1960) (describing Winthrop’s “belief that government was principally limited by the ruler’s conscience and self-restraint”). In Massachusetts Bay, “covenant was used to strengthen the authority of the state,” for in submitting to just government the members of the community “subjected themselves to obedience to God.” Indeed, “[c]arried into practice in Massachusetts, these doctrines resulted in a government in which authority was jealously held by the magistrates, intent upon carrying out the holy purposes of God’s word as expressed in the Bible.”

Second, the colony was deeply concerned about carefully navigating its relationship to England. For one, as a matter of theology, the early Puritans sought to reform the church from within and did not envision themselves as schismatics. On the ground, however, the Massachusetts Puritans instituted the practices of congregationalism, to which it was important not to draw royal attention.20Haskins, 13, 15, 44, 47–48 (“It was the intention of the Massachusetts leaders to find a middle way whereby doctrinal and other reforms could be accomplished without open separation.”). A related practical concern was the development of colonial law. The Massachusetts Bay charter authorized the colonial government to adopt its own legal structure, provided it “be not contrary or repugnant to the laws” of England.21Witte, 279.The early leaders of the Bay Colony were accordingly cautious about what legal provisions they codified in written law, which could “call to the attention of the crown colonial divergences from English law.”22Haskins, 36.

Within this basic framework of motivations—religious fervor and caution toward the motherland—the political and legal structure of the colony unfolded. The structure is rather nonintuitive. The charter had placed general management authority of the company in the General Court, consisting of the “freemen” or stockholders and the officers or assistants. The General Court quickly transferred much of its power to the Court of Assistants. In Haskins’ telling, this amounted to a “clear violation of the charter,” but it was not of concern to these leaders. The assistants, or magistrates as they came to be called, assumed essentially all powers of the government, including many of the powers of English justices of the peace. Until 1634, this power was concentrated in the hands of fewer than a dozen men, including John Winthrop, who dominated the early colony as governor. Also early on, the General Court opened its ranks somewhat by extending the status of “freeman” more broadly, but the leadership quickly narrowed this invitation to those “visible saints” who were members of the colony churches. While the General Court soon reclaimed its place as the primary governing body, the magistrates and the governor continued to wield extensive judicial powers.23Id. at 26–27, 29, 31–32. On the adjudicative powers of the General Court, see generally Barbara A. Black, The Judicial Power and the General Court in Early Massachusetts (1634–1686) (Ph.D. diss., Yale University, 1975). Within the General Court itself, a rivalry emerged between the more numerous deputies (elected from the freemen) and the more elite assistants (magistrates).24Haskins, 35; see also Francis J. Bremer, John Winthrop: America’s Forgotten Founding Father 304 (2003).

Early colonial law was developed largely through the orders and decisions of the magistrates.25Haskins, 119. Magistrates sat on all the colony’s courts of first instance, giving them an eye into what Winthrop would at times call the “dispositions” of the people.261 Winthrop’s Journal, 323; Haskins, 72 (noting the opportunity this presented “to observe at firsthand the kind of problems which affected the welfare of the colony as a whole” and “to mold the life of the communities through court orders”). But in administering justice, the magistrates “had few guidelines other than Scripture and their own sense of moral equity.”27Edgar J. McManus, Law and Liberty in Early New England: Criminal Justice and Due Process, 1620–1692, 4 (1993). Their primary role model was the English justice of the peace, but unlike justices of the peace—whose authority had at least some limits in their written commissions—the magistrates “had almost unlimited discretion in the administration of justice.”28Id.; see also George Haskins, “Lay Judges: Magistrates and Justices in Early Colonial Massachusetts,” in Law in Colonial Massachusetts, 1630–1800, 39, 44 (1984). Particularly in matters of crime and criminal punishment, they exercised broad and, in cases of political or religious dissidence, harsh discretion.29McManus, 5. The magistrates did not understand themselves as unbounded by law—on the contrary, they envisioned themselves as deeply embedded in a “fundamental law,” defined not only by “immemorial usages” but also, and principally, by the law of God as revealed in Scripture.30Haskins, 55–56; see also id. at 118 (discussing natural law ideas). Nonetheless, they guarded their power jealously.31E.g., Lawrence M. Friedman, Crime and Punishment in American History 32 (1993) (“[T]he judges, who were religious and political leaders, dominated the proceedings. They believed unswervingly in their right to rule in the name of God and according to the divine plan.”); Haskins, supra note 15, at 36 (describing the magistrates’ opposition to a written code of law because it would “put a bridle upon their own power and discretionary authority, which they regarded as necessary for the accomplishment of their tasks”), 44 (“[T]he magistrates . . . were the essence of lawfully and divinely constituted authority to which the people must submit in order that the covenant be kept.”). Winthrop, for example, argued that since God had specified penalties for certain offenses in Scripture, and since he surely could have specified penalties in others, God intended in cases not expressly controlled by Scripture for judges to exercise their “wisdom, learning, Courage” to prescribe penalties “pro re nata, when occation required,” though the sentence be not “obvious to Comon understanding.”32IV Winthrop’s Papers, 1638–1644, at 473 (Allyn Bailey Forbes ed., 1944).

By the mid-1630s, frustration at the expansive and discretionary powers of the magistrates set in motion efforts to reform the powers of government through a codification of basic law. As Winthrop recounts in his History of New England, in 1635, the deputies had “conceived great danger to [the] state” because the “magistrates, for want of positive laws, in many cases,” could “proceed according to their discretion.”33John Winthrop, 1 History of New England from 1630 to 1649, at 191 (James Savage ed., 1825). As a result, “it was agreed that some men should be appointed to frame a body of grounds of laws, in resemblance to a Magna Charta” and serving as “fundamental laws.”34Id. See also John Witte, Jr., “A New Magna Carta for the Early Modern Common Law: An 800th Anniversary Essay,” 30 J.L. & Religion 428, 438 (2015); Daniel R. Coquillette, “Radical Lawmakers in Colonial Massachusetts: The “Countenance of Authoritie” and the Lawes and Libertyes,” 67 New England Q. 179, 187 (1994). Beginning in 1635, multiple efforts to frame such a body of laws foundered, largely through the interference of Winthrop himself, who remained committed to the progressive and customary development of law through case-by-case adjudication.35Bremer, 305–06; see also Haskins, 116–17. It is from this struggle that Ward’s Body of Liberties, with its bail clause, emerged.

The Body of Liberties and Ward’s Bail Provision

Nathaniel Ward was among those selected to contribute to the work of drafting a legal code. And ultimately, a draft substantially identical to his proposed Body of Liberties was adopted by the General Council in 1641, over John Winthrop’s protests.36Bremer, 304–06. Ward’s draft was eventually adopted in place a competing draft composed by John Cotton. Cotton’s draft, entitled “Moses his Judicialls,” was based heavily on the Bible, deriving from scriptural sources the government’s authority “for all regulation of property rights, commerce, military affairs and punishment.”37Coquillette, 188. The emphasis in Cotton’s biblically oriented code was sources of government authority rather than the limitations of such authority. Béranger notes, interestingly, that Cotton’s draft largely overlooked the subject of judicial process, which was, by contrast, the longest of the sections of Ward’s Body of Liberties and the part in which the bail provision is located.38Béranger, 104–05.

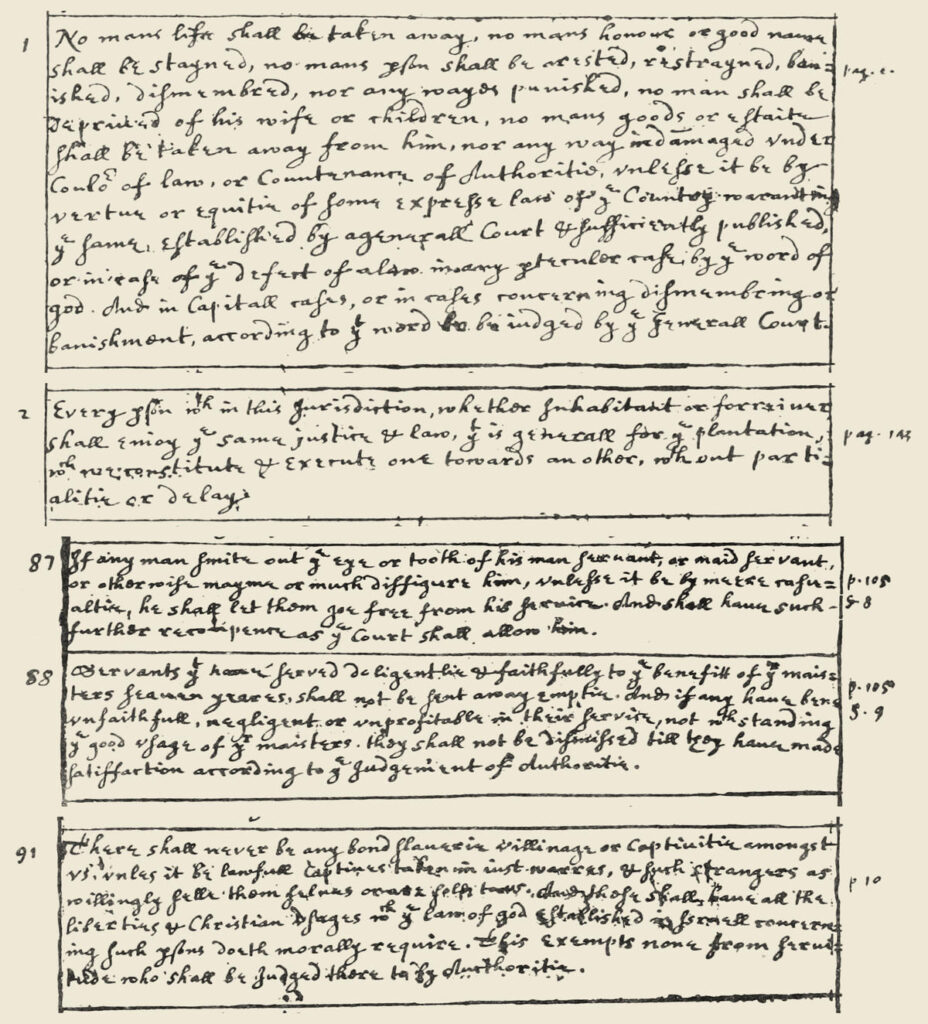

Ultimately, Ward’s draft was finished and circulated by 1639 and adopted by the General Court in 1641. It apparently “met with great approval”—almost all of its provisions were carried on into the Bay Colony’s 1648 code, Lawes and Libertyes.39Coquillette, 189–92. It is in the Body of Liberties, which came to be something of a fundamental or constitutional law to the Bay Colony, that Ward’s bail clause appeared. Liberty 18 provided:

Ultimately, Ward’s draft was finished and circulated by 1639 and adopted by the General Court in 1641. It apparently “met with great approval”—almost all of its provisions were carried on into the Bay Colony’s 1648 code, Lawes and Libertyes.39Coquillette, 189–92. It is in the Body of Liberties, which came to be something of a fundamental or constitutional law to the Bay Colony, that Ward’s bail clause appeared. Liberty 18 provided:

No mans person shall be restrained or imprisoned by any Authority whatsoever, before the law hath sentenced him thereto, If he can put in sufficient securitie, bayle, or mainprise, for his appearance, and good behaviour in the meane time, unlesse it be in Crimes Capitall, and Contempts in open Court, and in such cases where some expresse act of Court doth allow it.40The Massachusetts Body of Liberties (1641), in Puritan Political Ideas, 1558–1794, 177, 182 (Edmund S. Morgan ed., 1965).

Liberty 18 is notable in several respects. First, it is framed in prohibitory terms, subject to a combination of conditions and exceptions.41See Donald B. Verrilli, Jr., Note, “The Eighth Amendment and the Right to Bail: Historical Perspectives,” 82 Colum. L. Rev. 328, 343 (1982) (contrasting Liberty 18’s “explicit[] inten[tion] to secure pretrial liberty” with British bail statutes). The authorities are flatly prohibited from depriving any person of liberty before sentence provided that the person “put in sufficient securitie” and maintain good behavior. But the prohibition is lifted in “Crimes Capitall,” “Contempts in open Court,” and cases where an “expresse act” allows it. In other words, the circumstances in which magistrates may deny bail to an accused are sharply limited, constraining their discretionary authority. Second, those limitations are closely tied to written, codified provisions. Under Liberty 1, criminal offenses must be established in written law. And the most open-ended clause of Liberty 18—“where some expresse act of Court doth allow it”—nonetheless demands reference to explicit legal authority. This framework of limited magisterial discretion marks a significant shift from the English model.42See McManus, 97–98 (“The right to bail was better protected in the colonies than in England.”); Verrilli, 52.

Ward’s motivations in so crafting his bail provision may be gleaned from his legal and political commitments and the broader purposes of the Body of Liberties. But it should be noted at the outset that Ward was himself no “liberal” reformer: He believed in the divinely sanctioned authority of the magistrates and remained convinced that the common people had only a limited role in framing and directing the operations of government. Ward confidently affirmed the authority of civil government and was suspicious of efforts to shift political rule in anything approaching a democratic direction.43McDermott, 81–82. He also subscribed to the quasi-theocratic character of the Bay Colony project. In The Simple Cobbler, he disparaged at length the idea of religious toleration—or rather “Poly-piety,” which is “the greatest impiety in the world”—and he warned that “God doth no where in his word tolerate Christian States, to give Tolerations to such adversaries of his Truth, if they have power in their hands to suppresses them.”44Ward, A Simple Cobbler, 6–8. Concern for the liberty of religious dissenters, then, was far from Ward’s mind.

Ward subscribed to the covenantal and natural law theory of authority of the Bay Colony’s leaders—a “pure Protestant scholastic corporatism,” as McDermott characterizes it—but Ward introduced certain innovations to the vision.45McDermott, 171. For contemporaries like Winthrop and John Cotton, the author of the rival (and unsuccessful) codification of fundamental law, the divinely sanctioned authority of the magistrates sanctioned also their discretion, measured only by their discernment of Scripture’s express prescriptions and broader spirit. Winthrop hoped to set this discretion free to guide a customary development of law, with the magistrates in their wisdom discerning and guiding the “dispositions” of the people. This came with the added benefit of keeping law largely uncodified and thus not at risk of violating the charter proscription on adopting laws repugnant to the laws of England.461 Winthrop’s Journal, 323. And Cotton, in his rival draft, attempted to import directly the criminal framework he could discern from Scripture. But Ward’s Body of Liberties was a “colossal rebuke” of Winthrop’s policy of magisterial discretion and, moreover, a rebuke of a purely biblically derived legal code.47McDermott, 160–62, 177, 183.

Notwithstanding his intolerances and aristocratic sympathies, Ward had a deep sense of the legal boundedness of government and the organic unity of ruler and ruled.48E.g., Ward, The Simple Cobbler, 48 (“A King that lives by Law, lives by love . . . .”). Moreover, in contrast to the dispositions of Winthrop and Cotton, Ward was content to appeal to classical learning and non-religious thought.49At a meeting of the General Court in which he was invited to preach, Ward delivered a “moral and political discourse, grounding his propositions much upon the old Roman and Grecian governments,” which, to Winthrop, was “sure . . . an error,” since “religion and the word of God makes men wiser than their neighbors.” 2 Winthrop’s Journal: History of New England, 1630–1649, 36 (James Kendall Hosmer ed., 1908). Reflecting his broader legal outlook, Ward wrote in The Simple Cobbler, lamenting the civil strife in England, “In Civill warrs ‘twixt Subjects and their King, There is no conquest got, by conquering,” and he continued, “They that well end ill warrs, must have the skill, To make an end by Rule, and not by Will” (emphasis added). He then characterized the factions as “Majestas Imperii” and “Salus Populi”—the crown and the people, “the one fighting for Prerogatives, the other defending Liberties.” To Ward’s mind, “Civill Liberties and properties admeasured, to every man to his true suum, are the prima pura principia, propria quarto modo, the sine quibus of humane States.”50Ward, A Simple Cobbler, 43, 46 (“clear first principles, the basic element, the essential”). But Ward’s civil liberty sympathies do not sound in modern contractarian constitutionalism or democratic concern. When, during the process of considering Ward’s Body of Liberties, the draft was sent to all the towns for discussion by the people, Ward complained to Winthrop about his code being sent to “the common consideration of the people,” questioning “whether it be of God to interest the inferiour sort” in the framing of laws.51IV Winthrop’s Papers, 162–63; see also McDermott, 170–71 (noting that Ward clearly was “not motivated by concern for the lower classes or for democracy”); Béranger, 86–87 (1969) (noting that Ward was worried of an excess of democracy and defended the prerogatives of the ruling class). Ward emphasized that the people “may not be denied their proper and lawfull liberties,”52IV Winthrop’s Papers, 162–63. but the framing of just laws remained the prerogative of the superior classes.53Béranger, 87.

Rather, Ward’s liberties are grounded in reason, positive legislation, and God’s will.54See McDermott, 81. Again, in The Simple Cobbler, Ward argued that subjects “may fight against their Kings for their own Kingdomes, when Parliaments say they may and must: but Parliaments must not say they must, till God sayes they may” (emphasis added),55Ward, A Simple Cobbler, 44; see also id. at 45 (“Equity is as due to People, as Eminency to Princes: Liberty to Subjects, as Royalty to Kings . . . .”). demonstrating his commitment to positive legislative will bounded by the law of God. Shortly thereafter, Ward pointedly articulated his vision of authority:

Authority must have power to make and keep a people honest; People, honestly to obey Authority; both, a joynt-Councell to keep both safe. Morall Lawes, Royall Prerogatives, Popular Liberties, are not of Mans making or giving, but Gods: Man is but to measure them out by Gods Rule: which if mans wisdome cannot reach, Mans experience must mend: And these Essentialls, must not be Euphorized or Tribuned by one or a few mens discretion, but lineally sanctioned by Supreme Councels.56Id. at 48–49.

Ward conceded that in “pro-re-nascent occurrences, which cannot be foreseen,” accountable authorities “must have power to consult and execute against intersilient dangers and flagitious crimes prohibited by the light of Nature,” but he maintained, nonetheless, that “it were good if States would let People know so much before hand, by some safe woven manifesto . . . .”57Id. at 49; cf. IV Winthrop’s Papers, supra note 42, at 473 (“pro re nata, when occation required”) In short, Ward exhibited a deep distrust of a discretion that can verge toward the arbitrary; though legal authority remains embedded within the law of God, God’s plan for human political community dictates that law be measured not simply by the reason or judgment of the ruler but by reason reduced to explicit codification. Written law is not a concession to democratic assent but seems, for Ward, to follow necessarily from a covenantal and natural-law vision of lawfully bounded authority.

The Body of Liberties grounded and limited the authority of the government not only by the magistrates’ discretion and discernment of Scripture but by a rule of reason reduced to text. Coquillette notes that, structurally, the Body of Liberties was “organized, like a classical Roman code, by theoretical categories,” likely reflecting Ward’s classical learning.58See Coquillette, 191; cf. McDermott, 185 (describing the “corporatist” structure of the Body of Liberties). Ward, though recognizing the divinely sanctioned authority of rulers and more fundamentally the controlling authority of Scripture, nonetheless saw need to curtail civil authority with a written instrument.59Cf. McDermott, 177 (“[E]ven Ward’s code drew from Scripture for its justification. Nevertheless, lawmakers in colonial Massachusetts were intelligent enough to know that Scripture was subject to differing interpretations.”). The instrument embodies simultaneously an aversion to magisterial discretion and a due sense of deference to God and reason. In its preamble, the Body of Liberties states its intention to protect the “free fruition of such liberties Immunities and priveledges as humanitie, civilitie, and Christianitie call for as due to every man in his place and proportion.”60Body of Liberties, supra note 2, at 178–79; see also McDermott, surpa note 7, at 183 (noting the significance of Ward’s appeal to “humanitie” and “civilitie” alongside “Christianitie”). At Liberty 1, the instrument proscribes the deprivation of life, liberty, or property “unlesse it be by vertue or equitie of some expresse law of the Country warranting the same, established by a generall Court and sufficiently published, or in case of the defect of a law in any parteculer case by the word of God.” And in the case of capital and other grave offenses, punishment is only to be “according to that word to be judged by the Generall Court.”61Body of Liberties, 178–79. At the outset, then, Ward interposes a requirement of express authority between the magistrates and the deprivation of personal liberties and centralizes interpretive authority in the gravest cases. Consistent with his theological understanding of law, though, he permits appeal to Scripture in the event that positive law is absent or defective.

Liberty 18’s bail provision, then, flows from this program of limiting discretionary authority by written law. Liberty 18 takes a definite stance against the insistence of the magistrates upon the power to exercise broad judgment as to the dispositions of the people and the appropriate judicial response. Indeed, inasmuch as it relates to criminal process, it may be specifically responsive to the magistrates’ growing boldness in responding to grave criminal offenses. As Haskins notes, it was the magistrates’ progressive introduction of “discretionary penalties for major offenses,” making “the certainty of English practice appear[] undermined,” that elicited strong criticism of magisterial justice.62Haskins, Lay Judges, 47. Of course, it appears Ward’s response in Liberty 18 was not so much to restore the “certainty of English practice” as it was to significantly reform the inherited discretion of bail decisions. This is so even though Ward evidently conceived of his project as a compilation of the rights of Englishmen.63Witte, 442.

Though Liberty 18 fits naturally within Ward’s program of codification and constraints on discretion, its innovative character—in a code purporting to compile the established rights of Englishmen—raises questions as to more specific inspirations. As Béranger notes, however, it is difficult to discern exactly what legal sources Ward was working off when drafting the Body of Liberties. Béranger notes with confidence, however, that, in addition to “local usage,” Ward relied on the works of Sir Edward Coke, including his Reports and his 1628 Institutes.64Béranger, 92, 95; see also id. at 110 (arguing that Ward shows characteristics of Coke’s thought).The reliance on Sir Coke may suggest the relevance of his work A Little Treatise on Baile and Maineprize, though its publication in 1635 may slightly limit the likelihood of Ward’s familiarity with it.65Ward had left England for the Bay Colony in 1634. As a lettered and well-educated community, however, the Bay Colony may very well have had a copy of the work. The Little Treatise is a short statement of the law of bail and mainprize and is not, on its face, a model of reform. Two points, however, may be relevant to Ward’s purposes. First, it is a straightforward exposition of the relevant law, totaling about twenty pages in its 1637 edition. One could take from this, on the one hand, the value of a simple, single compilation of a law of bail, consistent with a program of codification. A different but not in compatible conclusion may be that, at twenty pages in its distilled (“Little”) version, the English law of bail was unduly complex, warranting simplification.66See Sir Edward Coke, Little Treatise of Baile and Maineprize, in The Selected Writings of Sir Edward Coke 569 (Steve Sheppard ed., Liberty Fund 2003 (1637)).

The second point concerns Coke’s conclusion to the Little Treatise. Though not obviously aimed at reform, the conclusion speaks to Coke’s wish to provide clarity to justices of the peace, so that they may “stand[] upon plaine & sure ground” in the administration of justice, “guided and directed by the rule of law.”In his discussion, he elaborates the delicate balance between law and discretion and the necessity that these “bee Concomitant”—“the one to be an accident inseparable to the other, so as neither Law without discretion, least it should incline to rigour, nor discretion without Law, least confusion should follow, should bee put in use.”67Id. at 569, 570. Coke thus tees up the issue of discretion as a matter of central importance in the administration of bail. Given Ward’s inclination toward written law as a bulwark against an already excessive magisterial discretion, Coke’s discussion may fairly have inspired a conclusion that only a discretion sharply circumscribed by text would truly be “an accident” to law, rather than law’s driving force.

Potentially of interest to Ward as well would have been a habeas corpus argument that John Selden made on behalf of his client Sir Edmund Hampden in 1627 (about seven years before Ward’s departure for Massachusetts).68John Selden, Speeches and Arguments, in 3.2 Opera Omnia 1934 (Lawbook Exchange 2006). Selden’s client was detained for “notable contempts” against the crown and for “the stirring up of sedition against the king,” and Selden sought to argue that, as charged, the offenses must be bailed. He claimed that “[a]ll offenses, by the laws of the realme, [are] of two kinds.” First, there are those offenses punishable by life or limb, including treason, murder, and felonies of lesser nature; second, there are offenses punishable by fine or damage and imprisonment, including “bloodsheds, affrays, and other trespasses.” For this first category, Selden suggested that judges “have not used to let” the defendant to bail, but that they do so in case of want of prosecution, lack of evidence, or similar circumstances—and so “a kind of discretion, rather than a constant law hath been exercised.” But if a defendant stands accused of “trespasses only, as all offences of the second kind are,” then, “by the constant course (unless some special act of parliament be to the contrary in some particular case) upon good offer of bail to the court, he is to be bailed” (emphasis added). Selden thus framed his argument to suggest two categories of offense for purposes of bail: serious offenses in which bail is discretionary, and less serious offenses in which a defendant must be bailed if he offers “good” sureties. From this starting point, Selden simply needed to argue that the contempt and the “stirring up of sedition” were but trespasses, falling within the category that had to be bailed.

Selden’s framing of his argument leaves some ambiguity as to the exact scope of the first class of offenses—wherein there is discretion concerning admittance to bail—with the inclusion of the phrases “felonies of lesser nature, and some more.” And he conceded that offenses in the second class—which, in his argument, “[are] to be bailed”—could be removed from that category by special act of Parliament.69Id. at 1939, 1940, 1948. But the basic structure of dividing the classes into two—one in which bail is to be granted with sufficient offer and another in which detention may be ordered by judicial discretion—mirrors the structure of Ward’s Liberty 18, including that clause’s permission for express laws that deny bail in cases other than capital offenses. If Ward was aware of Selden’s argument, it may have served as a more concrete example of method of framing discretion in the bail context.

Conclusion

Ward entered the Massachusetts Bay Colony in a moment of early struggle over the shape of the colony’s laws—in particular, struggle over the expansive and discretionary authority of the magistrates in judicial proceedings. Though he shared many of the legal, political, and religions commitments of the colony’s leaders, Ward’s own understanding of God’s injunction for a community bound by law led him to make a decisive contribution to the cause of written law—a codified law that constrained the discretion of magistrates not because of any commitment to democratic values but because in its nature authority is properly exercised subject to clear bounds. The bail provision of Liberty 18 in his Body of Liberties is a signal contribution to this cause of written constraint, reflecting a marked shift from the bail practice of England that so privileged judicial discretion. Ward’s bail clause thus advanced the development of a fundamental law centered on personal liberties but without parting from an older theological vision of law rooted heavily in a confessional understanding of God’s will for human political communities.

References

- 1Samuel Eliot Morison, Builders of the Bay Colony 233–34 (1930).

- 2The phrase appears in an editorial footnote in 1 Winthrop’s Journal: History of New England, 1630–1649, at 36 n.1 (James Kendall Hosmer ed., 1908).

- 3Morison, 234.

- 4Id. at 223, 226.

- 5John Ward Dean, A Memoir of the Rev. Nathaniel Ward, A.M., Author of The Simple Cobbler of Agawam in America 20 (1868); Jean Béranger, Nathaniel Ward 48 (1969); see also Scott A. McDermott, Body of Liberties: Godly Constitutionalism and the Origin of Written Fundamental Law in Massachusetts, 1634–1666, at 23–50 (Ph.D. diss., Saint Louis University, 2014) (describing a “Protestant Scholastic” worldview of the early seventeenth century).

- 6Nathaniel Ward, The Simple Cobler of Aggawam in America 60 (P.M. Zall ed., Univ. Nebraska Press 1969) (1647).

- 7Morison, 220–21.

- 8Id. at 221. John Ward Dean comments that “his charity [toward other religions] does not appear to have been enlarged by his experience abroad.” Dean, 10.

- 9Dean, 31; Morison, 222.

- 10John Spurr, English Puritanism, 1603–1689, at 81 (1998).

- 11Id. at 81–82; McDermott, 86.

- 12Morison, 222; Dean, 31.

- 13George Lee Haskins, Law and Authority in Early Massachusetts 60 (1960).

- 14Morison, 222.

- 15Haskins, 11–12.

- 16Id. at 4; see also id. at 114–15 (describing the colony’s relatively autonomous legal development).

- 17John Witte, Jr., The Reformation of Rights: Law, Religion, and Human Rights in Early Modern Calvinism 289 (2007); Avihu Zakai, Theocracy in Massachusetts: Reformation and Separation in Early Puritan New England 23 (1994); Haskins, 15, at 19 (“[T]he covenant was more than a social compact between men; it was a compact to live righteously and according to God’s word. God was therefore viewed as a party to the covenant.”).

- 18Witte, 289–90. Witte distinguishes the Puritans’ view from traditional Calvinist understandings, which saw the covenant of works as existing between God and the chosen people of Israel. Id.

- 19McDermott, 9–10; Haskins, 16 (“[Puritanism] assumed that its disciplines would regulate not only their own conduct but that of others, so that the world could be refashioned into the society ordained by God in the Bible.”); id. at 17 (noting Winthrop’s view that Christian liberty could only be maintained by subjection to authority); see also Note, The Rule of Law in Colonial Massachusetts, 108 U. Pa. L. Rev. 1001, 1035 (1960) (describing Winthrop’s “belief that government was principally limited by the ruler’s conscience and self-restraint”).

- 20Haskins, 13, 15, 44, 47–48 (“It was the intention of the Massachusetts leaders to find a middle way whereby doctrinal and other reforms could be accomplished without open separation.”).

- 21Witte, 279.

- 22Haskins, 36.

- 23Id. at 26–27, 29, 31–32. On the adjudicative powers of the General Court, see generally Barbara A. Black, The Judicial Power and the General Court in Early Massachusetts (1634–1686) (Ph.D. diss., Yale University, 1975).

- 24Haskins, 35; see also Francis J. Bremer, John Winthrop: America’s Forgotten Founding Father 304 (2003).

- 25Haskins, 119.

- 261 Winthrop’s Journal, 323; Haskins, 72 (noting the opportunity this presented “to observe at firsthand the kind of problems which affected the welfare of the colony as a whole” and “to mold the life of the communities through court orders”).

- 27Edgar J. McManus, Law and Liberty in Early New England: Criminal Justice and Due Process, 1620–1692, 4 (1993).

- 28Id.; see also George Haskins, “Lay Judges: Magistrates and Justices in Early Colonial Massachusetts,” in Law in Colonial Massachusetts, 1630–1800, 39, 44 (1984).

- 29McManus, 5.

- 30Haskins, 55–56; see also id. at 118 (discussing natural law ideas).

- 31E.g., Lawrence M. Friedman, Crime and Punishment in American History 32 (1993) (“[T]he judges, who were religious and political leaders, dominated the proceedings. They believed unswervingly in their right to rule in the name of God and according to the divine plan.”); Haskins, supra note 15, at 36 (describing the magistrates’ opposition to a written code of law because it would “put a bridle upon their own power and discretionary authority, which they regarded as necessary for the accomplishment of their tasks”), 44 (“[T]he magistrates . . . were the essence of lawfully and divinely constituted authority to which the people must submit in order that the covenant be kept.”).

- 32IV Winthrop’s Papers, 1638–1644, at 473 (Allyn Bailey Forbes ed., 1944).

- 33John Winthrop, 1 History of New England from 1630 to 1649, at 191 (James Savage ed., 1825).

- 34Id. See also John Witte, Jr., “A New Magna Carta for the Early Modern Common Law: An 800th Anniversary Essay,” 30 J.L. & Religion 428, 438 (2015); Daniel R. Coquillette, “Radical Lawmakers in Colonial Massachusetts: The “Countenance of Authoritie” and the Lawes and Libertyes,” 67 New England Q. 179, 187 (1994).

- 35Bremer, 305–06; see also Haskins, 116–17.

- 36Bremer, 304–06.

- 37Coquillette, 188.

- 38Béranger, 104–05.

- 39Coquillette, 189–92.

- 40The Massachusetts Body of Liberties (1641), in Puritan Political Ideas, 1558–1794, 177, 182 (Edmund S. Morgan ed., 1965).

- 41See Donald B. Verrilli, Jr., Note, “The Eighth Amendment and the Right to Bail: Historical Perspectives,” 82 Colum. L. Rev. 328, 343 (1982) (contrasting Liberty 18’s “explicit[] inten[tion] to secure pretrial liberty” with British bail statutes).

- 42See McManus, 97–98 (“The right to bail was better protected in the colonies than in England.”); Verrilli, 52.

- 43McDermott, 81–82.

- 44Ward, A Simple Cobbler, 6–8.

- 45McDermott, 171.

- 461 Winthrop’s Journal, 323.

- 47McDermott, 160–62, 177, 183.

- 48E.g., Ward, The Simple Cobbler, 48 (“A King that lives by Law, lives by love . . . .”).

- 49At a meeting of the General Court in which he was invited to preach, Ward delivered a “moral and political discourse, grounding his propositions much upon the old Roman and Grecian governments,” which, to Winthrop, was “sure . . . an error,” since “religion and the word of God makes men wiser than their neighbors.” 2 Winthrop’s Journal: History of New England, 1630–1649, 36 (James Kendall Hosmer ed., 1908).

- 50Ward, A Simple Cobbler, 43, 46 (“clear first principles, the basic element, the essential”).

- 51IV Winthrop’s Papers, 162–63; see also McDermott, 170–71 (noting that Ward clearly was “not motivated by concern for the lower classes or for democracy”); Béranger, 86–87 (1969) (noting that Ward was worried of an excess of democracy and defended the prerogatives of the ruling class).

- 52IV Winthrop’s Papers, 162–63.

- 53Béranger, 87.

- 54See McDermott, 81.

- 55Ward, A Simple Cobbler, 44; see also id. at 45 (“Equity is as due to People, as Eminency to Princes: Liberty to Subjects, as Royalty to Kings . . . .”).

- 56Id. at 48–49.

- 57Id. at 49; cf. IV Winthrop’s Papers, supra note 42, at 473 (“pro re nata, when occation required”)

- 58See Coquillette, 191; cf. McDermott, 185 (describing the “corporatist” structure of the Body of Liberties).

- 59Cf. McDermott, 177 (“[E]ven Ward’s code drew from Scripture for its justification. Nevertheless, lawmakers in colonial Massachusetts were intelligent enough to know that Scripture was subject to differing interpretations.”).

- 60Body of Liberties, supra note 2, at 178–79; see also McDermott, surpa note 7, at 183 (noting the significance of Ward’s appeal to “humanitie” and “civilitie” alongside “Christianitie”).

- 61Body of Liberties, 178–79.

- 62Haskins, Lay Judges, 47.

- 63Witte, 442.

- 64Béranger, 92, 95; see also id. at 110 (arguing that Ward shows characteristics of Coke’s thought).

- 65Ward had left England for the Bay Colony in 1634. As a lettered and well-educated community, however, the Bay Colony may very well have had a copy of the work.

- 66See Sir Edward Coke, Little Treatise of Baile and Maineprize, in The Selected Writings of Sir Edward Coke 569 (Steve Sheppard ed., Liberty Fund 2003 (1637)).

- 67Id. at 569, 570.

- 68John Selden, Speeches and Arguments, in 3.2 Opera Omnia 1934 (Lawbook Exchange 2006).

- 69Id. at 1939, 1940, 1948.