The Many Bails of Aaron Burr (1806-1808)

In the nation’s first decade, federal criminal prosecutions were exceedingly rare. The few bail decisions rendered by federal judges were largely unreported and left little mark on the law of bail in practice. And then came “The Great Case.”

In the nation’s first decade, federal criminal prosecutions were exceedingly rare. The few bail decisions rendered by federal judges were largely unreported and left little mark on the law of bail in practice. And then came “The Great Case.”

The defendant, Aaron Burr, was a former Vice President of the United States, best known as the man who killed Alexander Hamilton. Accused of treason, the most severe capital offense charged in the United States, Burr was a polarizing political figure. Newspapers reported the details to the interested masses. But perhaps no one was more interested in the trial’s outcome than Thomas Jefferson, the sitting president to whom Burr lost the bitter election of 1800 and was tasked with serving during his one-term stint as Vice President.

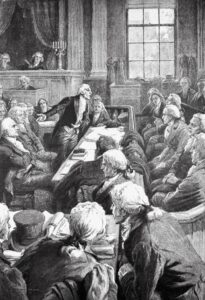

John Marshall, the sitting Chief Justice of the United States, presided over this “Trial of the Century.” Marshall had penned Marbury v. Madison, the cornerstone of modern judicial review, just four years earlier, and now had to try his best to protect the fledgling national government from treason while ensuring a fair trial to someone many already adjudged to be an enemy of the state.

Suspicion, Arrest, and Extradition

Aaron Burr was well-connected, the quintessential man about town. He was handsome and wealthy, with an elite education and a devoted political following, and he moved easily within New York and Washington’s privileged social circles. In 1806, he remained popular in Republican circles, despite losing both the 1800 presidential election and the 1804 New York governor’s race (the latter of which provided the impetus for his famous duel).

Despite his many connections, however, Burr found himself in a financial bind. He satisfied old debts with new credit, leveraging promises of future suretyship in exchange for relief, and his indebtedness led him down a path that ended in his trial for treason in 1807.

To this day, historians have not settled on what exactly Burr was up to. At the time, some accused him of planning to invade Spanish Texas; others thought he meant to lead a western secession movement. What is clear, though, is that he organized a quasi-military expedition to launch from Blennerhassett Island (located on the Virginia side of the Ohio River) and land outside of New Orleans.

In the autumn of 1806, the former vice president left for New Orleans to rendezvous with at least a hundred armed troops. Proceedings against him began before he reached the end of the Ohio River; Kentucky federal district attorney Joseph Hamilton Daveiss, alarmed, launched an irregular court motion in which he accused Burr of leading an illegal military expedition against Spanish dominions and asked the court to decide whether Burr should enter into a peace bond or appear in person to answer an indictment.

Burr opted to appear in person to quash the motion. The court ruled in his favor, declaring that preventative arrests were always unlawful, no matter how salutary their benefits. Arrest had to follow regular legal process, which had to be predicated on an illegal act already committed. Burr could not be arrested or held to a bond without an allegation of unlawful conduct and a grand jury presentment.

Proceedings were delayed until December, but Burr stuck around in Frankfurt anyway, and he was frequently spotted alongside the district judge at Republican dinner parties. When the grand jury convened on December 2, both Burr and his lawyer were in attendance, speaking up frequently to contest the prosecutor’s handling of the case. After three days, the grand jury ruled in Burr’s favor, and the Frankfurt notables threw another lavish ball that night to celebrate (again with the district judge among the guests of honor).

Burr left Frankfurt to assemble with his men, and he was promptly prosecuted once more. On January 16, 1807, the Attorney General of the Mississippi Territory confronted Burr and his men outside Bayou Pierre. Burr surrendered to civil authorities shortly thereafter.

Once again, the following proceedings had a marked informality about them. Thomas Rodney, the federal judge for the territory, privately said he would do all he could to keep Burr out of the potentially vengeful hands of his alleged co-conspirators. He assured Burr that should the military assert jurisdiction, he would “put on an old ’76 and march out in support of Col. B and the Constitn,” and then cajoled two local notables to stand surety for Burr in the amount of $2,500 each while Burr himself pledged $5,000. None of these arrangements seem to have been in writing at the time. Instead, Judge Rodney himself wrote up the recognizances several days later, signing them in his own hand. Burr was once again wined and dined by the local Federalists until the grand jury convened on February 3.

Burr again attended the proceedings in person, and he got more than his expected vindication. The jury not only refused to indict Burr “of any crime or misdemeanor,” it presented a denouncement of local authorities for engaging in “military arrests, made without warrants” and “destructive of personal liberty.” Judge Rodney, taken aback, refused to release Burr from his recognizance and ordered him to appear at the next court session to face a fresh grand jury.

Burr fled back to Bayou Pierre while his counsel argued that a recognizance could not be maintained after a jury’s refusal to indict. Almost two weeks later, he was captured while attempting to flee the territory in the vicinity of Fort Stoddard. The military took jurisdiction (Judge Rodney remained in Natchez, along with his old ‘76) and held Burr in the fort, where he could still receive visitors and play chess with the local notables. Following an extradition order and a long journey, Burr arrived in Richmond for the spring term of the federal circuit court on March 26, 1807.

Pre-Indictment Proceedings

It was an oddity of federal procedure at the time that the Chief Justice of the United States could find himself playing the role of justice of the peace, deciding questions of probable cause and setting bail. But Virginia was within John Marshall’s assigned circuit, and he lived in Richmond when the Supreme Court was not in session. Upon hearing the news that Burr had arrived in Richmond, Marshall traversed the few blocks from his home to the Eagle Tavern and interviewed him in a private room.

Spurred on by President Jefferson himself, the government pressed for Burr’s committal to jail pending trial at every available opportunity. As arguments and rulings proceeded after the initial hearing, Marshall preliminarily admitted Burr to bail on a $5,000 bond pending rulings on several larger questions surrounding whether to commit him pending trial.

Marshall’s anchor was the text of the First Judiciary Act, which as we have seen followed the dissenter’s model for bail: “And upon all arrests in criminal cases, bail shall be admitted, except where the punishment may be death, in which cases . . . [a judge or justice] shall exercise their discretion therein, regarding the nature and circumstances of the offence, and of the evidence, and the usages of law.” Since the Government was charging treason—a capital offense—as well as misdemeanor conspiracy, the two charges had different applications under the statute. Marshall never wavered from his view that on the misdemeanor charge Burr had an absolute entitlement to be released. If Burr could not procure sureties in the amount demanded by the court, he encouraged Burr to return (within a day or less) to have the amount adjusted downward.

Chief Justice Marshall was in a politically awkward position – informing his discretion in admitting Burr to jail effectively meant that he had to pre-judge the case. However, he avoided much of this awkwardness with another Marbury-like epiphany: The court need not scrutinize the probability of guilt if it did not have jurisdiction to proceed on an arrest made without probable cause, and since all the government could proffer was an encrypted letter whose authenticity could not be established, Marshall ruled that there was no probable cause to arrest Burr on treason.

The capital charge set aside, Burr had to be admitted to bail on the misdemeanor charge under the Judiciary Act. Perhaps to mollify the Government after the probable cause ruling, Marshall set bail at the extraordinary sum of $10,000—that is, a $10,000 bond required of Burr and $10,000 worth of bonds aggregated across whatever sureties he could find. By the end of the day, Burr and five sureties posted the bonds with the court.

Burr was free to return to his lodgings at the tavern, which he left later in the spring for his counsel’s rented apartment across the street. As the grand jury assembled and rumors grew that a star witness was drawing nearer to Richmond, the Government renewed its motion to commit Burr to jail on the charge of treason, arguing that Burr was a flight risk. Speaking in his own defense, Burr brokered a compromise: Marshall would let the question of probable cause go to the grand jury, the Government would drop its motion for committal in the meantime, and Burr would post an additional bond of $10,000 with four new sureties.

Post-Indictment Proceedings

Burr’s luck with juries ran out in Richmond. On June 24, the grand jury returned true bills for the re-argued misdemeanor indictment and treason charge. The Government immediately renewed its motion to commit Burr to jail.

Whether a federal court retained discretion to bail after a grand jury indictment was a question of first impression on which even the Government’s lawyers could not agree. The lead prosecutor argued that the court possessed the power but that it had to be “deliberately and cautiously exercised,” but renowned oral advocate William Wirt disagreed, arguing that the people spoke through the grand jury, not the Chief Justice.

Burr’s counsel responded that admitting to bail was an inherent power of courts and raised several practical difficulties with Wirt’s position. The Government had conceded that courts could bail after arrest, but some arrests happened only after grand jury indictments – if defendants arrested after indictment could be bailed by the express terms of the Judiciary Act, why not those arrested before indictment?

In the end, Marshall adhered closely to the text of the Judiciary Act, ruling that “there was no distinction between treason and other criminal cases, as to the power to bail upon arrests.” But there was one more issue: the Judiciary Act instructed courts to follow the common law, and Marshall doubted the existence of any precedent concerning the bailing of indicted traitors. With neither side prepared to present American case law, Marshall suspended final judgment until precedents could be produced.

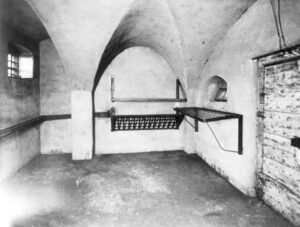

Perhaps in the mistaken belief that trial was imminent, Burr offered to enter the Richmond jail so as not to sidetrack proceedings on a tertiary legal issue. He immediately regretted his decision, and his counsel moved to pay the expenses of alternative confinement and the posting of a guard. Burr moved back into his lawyer’s dining parlor (newly outfitted with barred windows, padlocked doors, and a round-the-clock seven-member guard) less than two days later.

After the weekend, though, it was the government’s turn to protest. Marshall opted for a Solomonic ruling: until trial began, Burr would stay at the newly-constructed penitentiary outside of town; once trial began and daily conferences with counsel were necessary, he could return to the padlocked dining room across from the courthouse. Burr was relocated to the penitentiary, where he remained through the entire month of July.

Compared to the city jail, the penitentiary was virtually a private retreat. According to one biography, Burr “had a suite of three rooms in the third story, extending one hundred feet, where he was allowed to see his friends without the presence of a witness.” The Richmond population sent him a steady supply of gifts and his daughter Theodosia stayed overnight at least once. The jailor kept up a running joke asking Burr’s permission to lock him in at night.

After the Verdict

The treason trial concluded on September 1. The jury took little time to return a verdict of not guilty – the government’s key evidence had turned out to be a forgery, and their star witness had been discredited in a blistering cross-examination. Although this is where most accounts of the trial end, Burr’s misdemeanor conspiracy charge remained pending and his prosecutors were not yet finished making arrangements with his sureties.

This time, Burr’s counsel insisted that the court answer an argument Marshall had first brushed aside: that Burr need not pledge any security at all, because the laws of Virginia did not permit arrest on misdemeanor charges alone. Marshall wrestled with the question for two days. Ultimately he concluded that federal criminal practice could not depend on the vagaries of state rules. Section 33 of the Judiciary Act clearly contemplated arrest and bail on any charge, and general common law practice—not in Virginia, but in England—had evolved to permit arrest process (capias) for misdemeanor offenses. But most powerful for Marshall was the analogy to civil bail. How strange it would be if Burr could be arrested and held to bail for a debt but not for a federal criminal charge, the punishment of which was a substantial term of incarceration. Marshall ruled that Burr had to be released, but also that a sufficient recognizance had to be taken.

What did a sufficient recognizance look like now? Burr had been acquitted of treason. The Government, pointing out that the verdict depended on the lack of evidence excluded on technical grounds, argued that the likelihood of Burr’s guilt should weigh heavily in the calculation of a sufficient surety.

But Burr had already separately pledged two bonds of $10,000 in the course of the proceedings. Speaking personally to the court, Burr complained that Burr complained that “he was not able to give bail in as large a sum as he had given at first; that his ability being lessened, the same sum would be now much more oppressive than it had been then.” His counsel followed on with the argument that sufficiency of a surety had to be measured not by the charge but by the accused’s property.

Marshall was cagey in his ruling. He observed that “[c]laims of a civil nature have come against [Burr] which have necessarily increased the difficulty of his procuring bail in this case,” but Marshall claimed that this circumstance did not influence his ruling. Instead he pronounced his conviction that “I always thought, and still think, the former bail a very high sum.” Concerned that $10,000 had itself been an excessive bail in violation of the Constitution, Marshall ruled that he “shall therefore be contented with bail in the sum of five thousand dollars.” With bonds posted the same day, Burr’s two-month confinement came to an end on September 3.

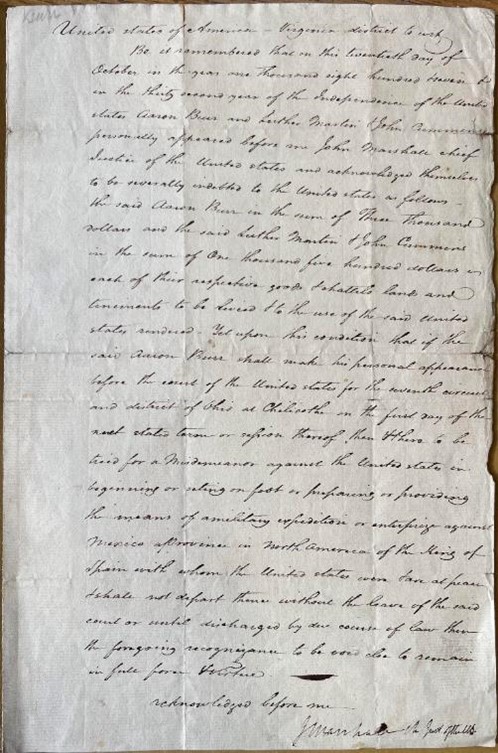

Still the case was not ended. Marshall, having stricken most of the key evidence, essentially entered a directed verdict on the misdemeanor charge on September 9. After more than a month of further argument concerning whether the Government could bring the prosecution again in another venue where it could gather better evidence, Marshall ordered Burr and a co-conspirator, Harman Blennerhasset, bound for re-trial in the district of Ohio. Instead of committing either to the custody of the marshal, the court accepted bails of $3,000 each to secure their appearance.

When the circuit term opened in Chillicothe on January 23, 1808, Burr and Blennerhassett were thousands of miles away. Even after Burr had fled to Paris in June 1808, newspapers continued to report rumors of his daily arrival in Ohio to vindicate his sureties. But it was not to be. Neither Burr nor Blennerhassett ever submitted to the circuit court’s jurisdiction, while the Government, embarrassed enough over the treason trial in Virginia, quietly gave up the Ohio prosecution.

What then became of Burr’s final bail? Despite the forfeiture, there is no evidence the Government ever collected a dollar from Burr, Blennerhassett, or any of their sureties. The Ohio court duly notified the attorney general of the forfeiture, but no action to recover the debt appears to have commenced, and no receipts for a forfeited bail appear on the Treasury rolls. Such was the expected outcome for the defendants. In October 1807 Blennerhassett wrote to his wife describing his and Burr’s plans to forfeit their Ohio recognizances. He informed her that a local lawyer “can explain to you how two writs of scire facias mut be returned, in case of my absence from the district, before my recognizance becomes forfeited.” Since the court held only two terms a year, the earliest execution proceedings could even commence would be January 1809, long after the Government would have lost interest in the case—and in seeing its many failures in the Burr affair rehearsed again in the newspapers.

To sum it up at last: Through the course of his prosecution for treason and conspiracy, Aaron Burr pledged bail bonds of $5,000, $5,000, $10,000, $10,000, $5,000, and $3,000 on separate occasions. The first and the last bails were forfeited when Burr violated court orders to attend the next session of court. Yet in all this, Burr never paid a single dollar to the court, the Government, or his sureties. He was detained for two months (in especially generous accommodations) after a grand jury indictment for treason, the most serious capital offense chargeable. But at all other times the Chief Justice of the United States and even the Government’s own prosecutors understood that Burr had a right to be released pretrial upon a pledged amount he could reasonably access.

What We Can Learn

The first major treason prosecution in the United States was of course unique in many ways. Yet the administration of the federal bail system in the Burr trial seems to have run along ordinary paths. In three respects, the Burr case illustrates well how bail worked in practice for first-class citizens.

First, admission to bail was a function of class, not cash. It bears repeated emphasis that neither defendants nor their sureties paid anything upfront to the court admitting them to bail in the Founding Era. A surety’s sworn declaration of his property holdings did not secure collateral to the court nor create any kind of lien that could be easily foreclosed. Access to sureties thus did not turn on a defendant’s liquidity. Rather, the question for a potential surety was not one of financial risk but of reputational risk. A surety who pledged for an absconding defendant was unlikely to even forfeit any property in the end, but the pledge sent a social signal of the surety’s improvidence, lack of judgment, and questionable reliability in future transactions.

Second, forfeiture burdened the government, not bailees. The second lesson follows the logic of the first. Since neither defendants nor their sureties posted real collateral in making their recognizances, there was usually nothing within easy reach for the government to collect upon forfeiture. In our modern system, collateral is often taken upfront, ahead of a defendant’s release. Defendants may pay the full amount of the bond in cash into the registry of a court before they are released. Other times, commercial bondsmen take collateral, often in the form of title liens on cars or real property, before posting a financial instrument with the court that allows for a defendant’s release. But in the Founding Era, and through the first half of the nineteenth century, title and possession of virtually all property remained in the hands of defendants and their sureties up until the government completed the tortuous process of executing a creditor’s remedy at law.

Finally, defendant safeguards were as strong in practice as they were on the books. In sum, the chief lesson of the Burr trial was that the dissenter’s model of bail worked largely as intended, at least for first-class citizens.