A Philadelphia Story: The Saga of Patrick Lyon (1798)

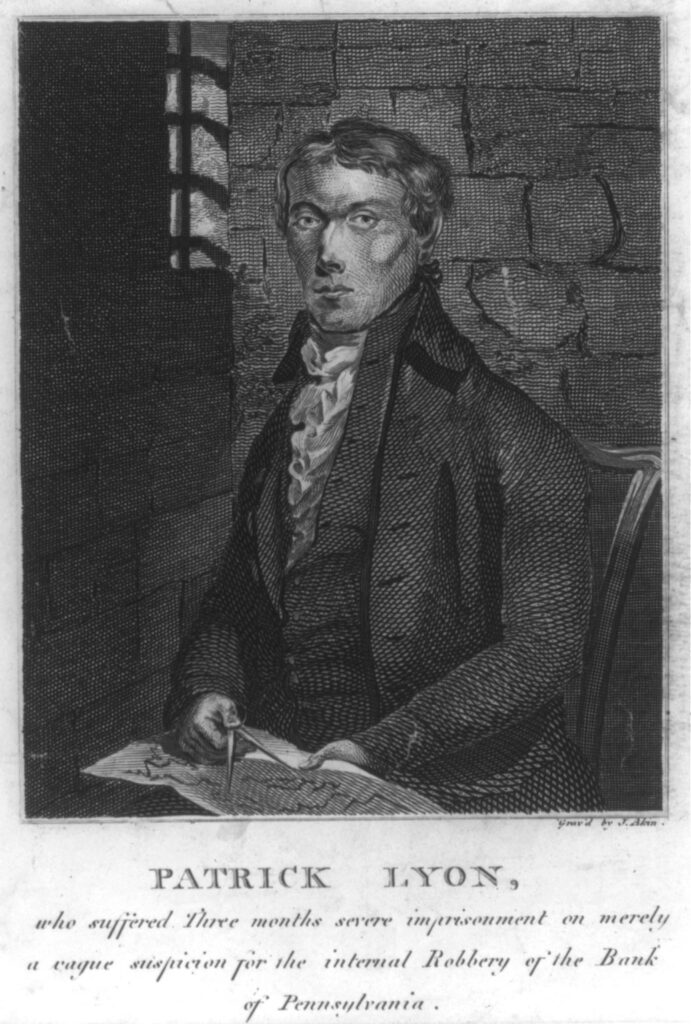

On the night of Saturday, August 31, 1798, someone robbed the Bank of Pennsylvania. It was the nation’s first bank heist. The Bank had recently been relocated to Carpenter’s Hall—because of security concerns at its former location, ironically—and new vault doors and locks had been installed.1Thomas Llyod, The Robbery of the Bank of Pennsylvania. The Trial in the Supreme Court of the State of Pennsylvania. Reported from the Notes by T. Lloyd. Upon which the president of that bank, the cashier, one of the directors (who was an alderman) and another person who was the high constable of Philadelphia; were sentenced to pay Patrick Lyon, twelve thousand dollars damages, for a false and malicious prosecution against him, without either reasonable or probable cause, 44 (1808) On the morning of September 1st they were swinging open. The intruders had stolen $162,821 in bank notes and gold, the equivalent of more than five million dollars today.2Ron Avery, America’s First Bank Robbery, Carpenters’ Hall, https://www.carpentershall.org/americas-first-bank-robbery (last visited Nov. 18, 2021); T. Lloyd at 12; CPI Inflation Calculator, https://www.in2013dollars.com. Suspicion fell on the blacksmith who had forged the new locks, Patrick Lyon.

On the night of Saturday, August 31, 1798, someone robbed the Bank of Pennsylvania. It was the nation’s first bank heist. The Bank had recently been relocated to Carpenter’s Hall—because of security concerns at its former location, ironically—and new vault doors and locks had been installed.1Thomas Llyod, The Robbery of the Bank of Pennsylvania. The Trial in the Supreme Court of the State of Pennsylvania. Reported from the Notes by T. Lloyd. Upon which the president of that bank, the cashier, one of the directors (who was an alderman) and another person who was the high constable of Philadelphia; were sentenced to pay Patrick Lyon, twelve thousand dollars damages, for a false and malicious prosecution against him, without either reasonable or probable cause, 44 (1808) On the morning of September 1st they were swinging open. The intruders had stolen $162,821 in bank notes and gold, the equivalent of more than five million dollars today.2Ron Avery, America’s First Bank Robbery, Carpenters’ Hall, https://www.carpentershall.org/americas-first-bank-robbery (last visited Nov. 18, 2021); T. Lloyd at 12; CPI Inflation Calculator, https://www.in2013dollars.com. Suspicion fell on the blacksmith who had forged the new locks, Patrick Lyon.

Lyon was no longer in the city; he had fled the annual scourge of yellow fever. The year before, it had killed his wife Ann and their infant daughter, Clementina. In August of 1798, after completing his work for the Bank, Lyon took his apprentice Jamie and traveled to Delaware. For Jamie it was too late; he fell ill with yellow fever on the journey and died within a few days.3Lyon wrote “it is wrong to reflect, but the loss I sustained from this promising youth, I am certain I shall never retrieve.” Patrick Lyon, The narrative of Patrick Lyon, who suffered three months severe imprisonment in Philadelphia gaol; on merely a vague suspicion, of being concerned in the robbery of the Bank of Pennsylvania: with his remarks thereon, 11-13 (1799).

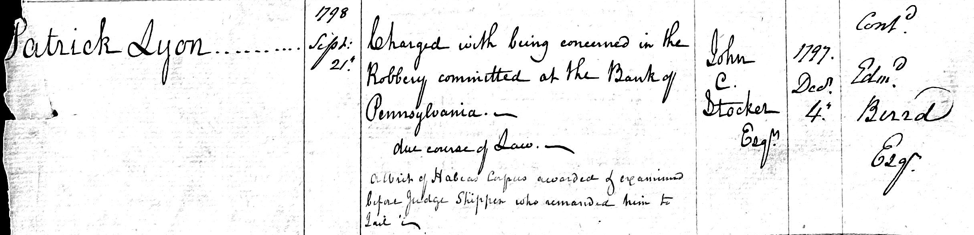

When Lyon heard that the Bank had been robbed and that he was suspected, he returned to Philadelphia. He met with Samuel M. Fox, president of the bank; John Clement Stocker, a bank director and a Philadelphia alderman; Jonathan Smith, cashier of the bank; and Robert Wharton, the mayor, at Stocker’s house on September 21st. Lyon protested his innocence and told the group that he suspected a man named Isaac Davis, who had visited his workshop while he was constructing the locks and made strange comments. The men were not convinced. As Wharton later testified: “Lyon gave a history where he had been, but he told such a straight and well connected story that I was sure he was guilty.” Stocker, in his capacity as alderman, ordered Lyon to procure sureties in the amount of $150,000 or suffer commitment.4Lloyd, 8-9, 44. It was not possible for anyone to procure sureties in that amount, let alone a blacksmith. Lyon was committed.5Prisoners for Trial Docket 1798-1802, 63 (Phila. City Archives). He filed a habeas corpus petition, and on October 29, Chief Justice Shippen of the Pennsylvania Court reduced his bail to $6,000, but Lyon’s friends were wary of coming to his aid. He remained in jail.6Lloyd, 69.

The authorities began to suspect that Isaac Davis might be the real perpetrator when he began to deposit large quantities of the bank’s stolen notes at….the same bank. They confronted Davis, threatened arrest, and offered a pardon for his cooperation. Davis confessed. He reported that his only accomplice had been Thomas Cunningham, the bank porter on duty the night of the robbery, who had since died of yellow fever. Davis had nearly all of the stolen funds in his possession and returned them. Still, Lyon was not released. Once again he succeeded in obtaining a bail reduction via a habeas petition, from $6,000 to $2,000. This time, he was able to find sureties.7Lloyd, 14, 76. After two grand juries declined to return a true bill against him, the bank authorities gave up.

Lyon did well in the end. He sued Fox, the bank president; Stocker, the director and Alderman; Smith, the bank cashier; and Philadelphia’s high constable, John Haines, for malicious prosecution and false imprisonment. When the jury read its verdict—$12,000 for Lyon—the spectators erupted into cheers. The judge scolded the spectators for acting like they were in a “playhouse.” The record of the civil trial offers a detailed window on both criminal and civil procedure in 1790s Pennsylvania. Lyon wrote an account of his experience that made him a popular hero. The defendants moved for a new trial but ultimately settled for $9,000.8Lloyd, 197. Lyon turned his professional energies to the engineering and construction of water-pumping fire engines and became a successful inventor and businessman. He remarried, commissioned a portrait by John Neagle that is considered a landmark of American portraiture, and lived to sixty.9Lyon, 5-6

Lyon’s case suggests that, whatever the law books said, not everyone who was entitled to release on bail had meaningful access to it, and that magistrates did occasionally use bail as an instrument of detention rather than release, just as in the present. It illuminates the tight network of men who operated the city’s institutions and their overlapping roles; no one seems to have blinked at a Bank director issuing a judicial commitment order in the robbery case involving his bank. And Lyon’s case suggests that the writ of habeas corpus did function as a mechanism of oversight and accountability for pretrial incarceration.

References

- 1Thomas Llyod, The Robbery of the Bank of Pennsylvania. The Trial in the Supreme Court of the State of Pennsylvania. Reported from the Notes by T. Lloyd. Upon which the president of that bank, the cashier, one of the directors (who was an alderman) and another person who was the high constable of Philadelphia; were sentenced to pay Patrick Lyon, twelve thousand dollars damages, for a false and malicious prosecution against him, without either reasonable or probable cause, 44 (1808)

- 2Ron Avery, America’s First Bank Robbery, Carpenters’ Hall, https://www.carpentershall.org/americas-first-bank-robbery (last visited Nov. 18, 2021); T. Lloyd at 12; CPI Inflation Calculator, https://www.in2013dollars.com.

- 3Lyon wrote “it is wrong to reflect, but the loss I sustained from this promising youth, I am certain I shall never retrieve.” Patrick Lyon, The narrative of Patrick Lyon, who suffered three months severe imprisonment in Philadelphia gaol; on merely a vague suspicion, of being concerned in the robbery of the Bank of Pennsylvania: with his remarks thereon, 11-13 (1799).

- 4Lloyd, 8-9, 44.

- 5Prisoners for Trial Docket 1798-1802, 63 (Phila. City Archives).

- 6Lloyd, 69.

- 7Lloyd, 14, 76.

- 8Lloyd, 197.

- 9Lyon, 5-6